Earlier this week, Scioto Analysis released a new report on Human development in Ohio. For this project, we partnered with students from Ohio State University to collect data on income, education, and health across Ohio in order to see how well Ohioans are doing across the state.

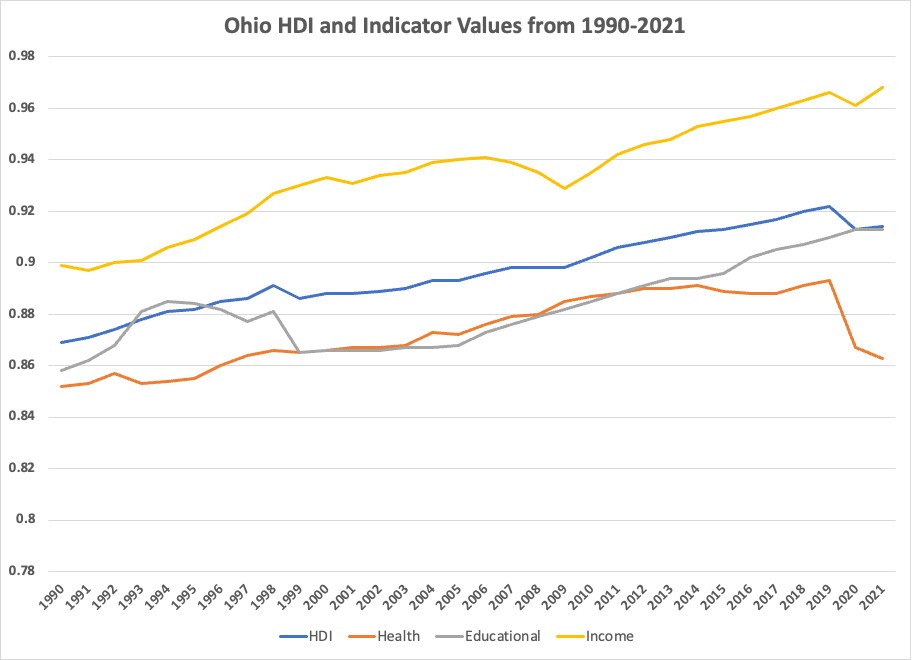

The Human Development Index works by creating indexes for income, education, and health then estimating the average of the three as the final result.

The closer the Human Development Index value is to one, the closer that state is to the maximum value for that indicator (e.g. the closer Ohio’s median income is to the maximum median income in the US). This suggests high overall levels of income, education, and health. Conversely, the closer it is to zero, the closer it is to the minimum values for income, education, and health.

Human development decreased during the pandemic

From the chart below, we can see that overall, human development has increased in Ohio since 1990. The main exception is a slight drop in 2020, where the indicators for health and income fell noticeably. The result is that human development as a whole was lower during the pandemic.

Much of this fall was driven by a drop in the health indicator. This indicator is based on life expectancy, so it should be unsurprising that it fell during the pandemic. Additionally, we see a slight decrease in the income indicator, likely due to the recession sparked by COVID-19. Again, the pandemic is certainly to blame.

Looking forward, we can see that the biggest area for improvement in Ohio is in the health indicator. We should expect some catch-up effect as we become further removed from the pandemic, but even then it stands out as an area that policymakers could address.

We might also expect the pandemic to have a delayed effect on education outcomes. The education component of the human development index is derived from two data points: the average years of schooling for adults and the expected years of schooling for young children.

We know that the pandemic has resulted in decreased test scores across the country, but it is unclear how that will translate into future pursuit of education. Our recent study on school spending suggests that lower test scores may decrease the number of people who attend college.

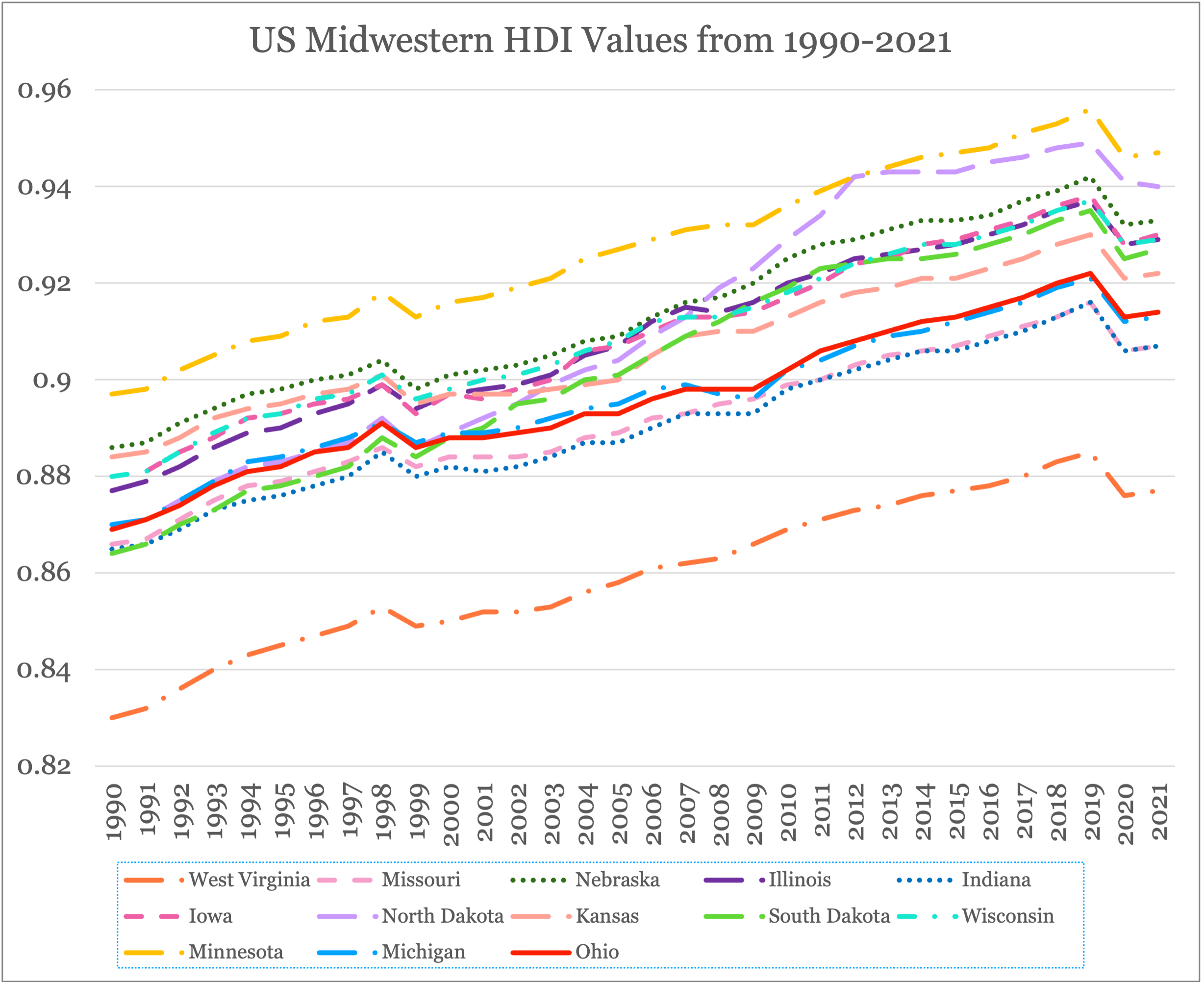

Other Midwest states

Another takeaway from the report is that Ohio lags behind many of its neighbors when it comes to the Human Development Index. Currently, only Kansas, Missouri, Indiana, and Michigan rank lower than Ohio within the Midwest region.

Much of the Midwest has followed the same trend line as Ohio. A steady increase, with dips around 1999, 2008, and most recently 2020. One thing that has remained constant is the gap between states.

This is somewhat surprising, mostly because of how close these states are to the maximum value already. I initially suspected that because there wasn’t much room for the states at the top to improve, we would see the states near the bottom catch up. I still think there will be diminishing returns at some point (there is a ceiling on the Human Development Index), but it will be interesting to see how close to one these states can get before they start to taper off.