In July of 2023, my cousin got married. This was an exciting time for my family because she was the first of our generation to get married. But she didn’t legally get married in July–that’s just when she had the ceremony. As far as the state of Missouri is concerned, she had been legally married since April.

You may have been able to guess this based on when she chose to get married, but my cousin and her husband wanted to file their taxes jointly in 2023. She was just finishing up her time in med school, so they were living almost exclusively off of her husband’s salary at the time. This meant that by filing jointly, they ended up paying less income tax.

This phenomenon is often referred to as the marriage bonus, and it comes from the fact that in the eyes of the government, marriage is an important financial contract. Because married couples share all of their resources, they get to add their income together when filing taxes and are treated as a single unit. A married couple where both partners earn $50,000 a year would pay the same amount of taxes as one where a single earner makes $100,000 a year.

The main reason this can lead to such a big decrease in taxable income is because we have progressive income tax brackets. Married couples essentially double the size of those income brackets and end up paying less as a result.

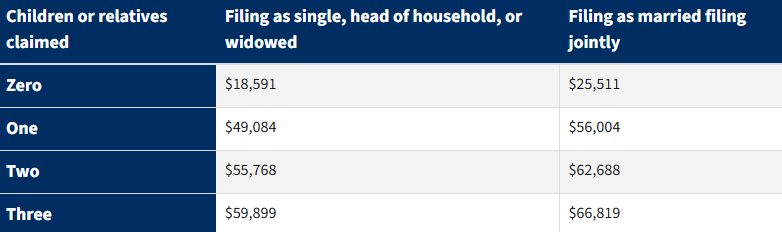

On the other hand, some couples can incur a marriage penalty if combining their incomes makes them ineligible for certain tax credits. Take the Earned Income Tax Credit for example. Below is a table from the IRS showing the income eligibility thresholds:

Under the wrong circumstances, married couples can lose thousands of dollars in tax credits by filing their taxes together. As the number of children increases, the threshold for joint filers to receive the Earned Income Tax Credit becomes relatively closer to the threshold for single filers. This means that families with more children face even more severe marriage penalties than those with fewer children.

Some couples can also see marriage penalties if both partners are high earners and have similar incomes. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lessened this penalty for middle- and high-income families, though in some cases they could lower their tax liability by filing separately.

A 2018 analysis from the Tax Policy Center found that 43% of married couples receive a marriage bonus, and 43% of married couples receive a marriage penalty. The average bonus was $3,062 compared to if those couples filed separately, and the average penalty was $2,064.

Last year at the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management annual conference, I listened to a roundtable discussion about tax policy. In one of the opening remarks, a presenter talked about how tax policy is often viewed as an accounting problem, with little attention paid to how it shapes the way we live.

Marriage bonuses and penalties reward couples that are able to live off the salary of one individual. This implicitly punishes couples who rely on two incomes to get by. While this is technically an avoidable problem (couples could file their taxes separately), it’s extremely difficult to know whether or not that would actually lead to savings for some people. It definitely will lead to more work and confusion that comes with filing taxes in the first place.

This quirk of the tax code is another example of how interconnected all aspects of public policy really are. A seemingly innocuous decision like allowing married couples to file their taxes together can reward people for tying the knot–or punish them for it.