In my first semester of college I took a class on the philosophy of law. We went through the history of philosophers discussing why we have laws and what enforcing them did for society. This is a gross oversimplification, but most of these philosophies essentially boiled down to “we don’t want people to commit crimes because that is inherently wrong and it doesn’t fit in with our broader social norms. This is why when people break the law, we punish them.”

I did quite poorly in this class so I couldn’t explain more of the nuance even if I wanted to, but these ideas about crime and punishment left me feeling unsatisfied. It wasn’t until later when I was exposed to the economic theory behind crime that I felt like I began to agree with a general understanding of why crime is a problem and what our society could do about it.

So, I’d like to provide a brief introduction to the way that economists think about crime and the criminal justice system. These are the broad ideas of why economists think crime is a negative part of our society, why people choose to do it, and what policy options we have for reducing crime.

Why crime is an economic problem

At Scioto Analysis, we think a lot about the value that non-market activity has on the economy. Generally, we think of non-market activity as an addition to the formal economy because people who participate in non-market activity are adding value despite the fact that they are not being formally compensated.

Criminal activity is different from other forms of non-market activity because it largely falls under the umbrella of “rent-seeking behavior.” Rent-seeking is a poorly worded term that has nothing to do with our general understanding of what rent is, but instead describes activity that benefits one individual but does not create any additional value for society. While rents are traditionally earned by ownership of a resource, rent-seeking behavior is characterized by manipulation of markets to gain an advantage that siphons resources from others.

Stealing is a good example of rent-seeking because the person who steals receives some benefit for themselves, but that benefit strictly comes from another part of the economy. In fact, stealing is likely to shrink the overall economy, since other people now have to spend some money on security systems to prevent falling victim, an otherwise unnecessary drag on their capacity to get the things they want.

Crime through an economic lens

In order to think of economic solutions to the problem of crime, we need to understand the incentives that exist for people to choose criminal activity in the first place. To do this, we will construct a very simple decision model.

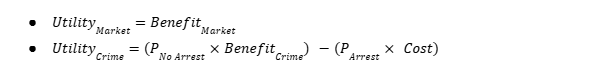

Consider an individual whose goal is to maximize their individual utility. To do this, they get to decide whether they will participate in criminal activity, or alternatively some sort of formal market activity. We can describe their utilities very simply with the following functions:

In the first equation, the individual’s utility is exactly the value they expect to get from their regular market activity. This could easily be thought of as the wage they expect to earn by working some job. The key assumption here is that this value is fixed for our individual, and it is easily known.

In the second equation, this person’s utility relies on the probability that they will be arrested for committing a crime. If this person is arrested, they gain no utility and instead incur some negative cost associated with being arrested. If they are not arrested, then they receive the full benefit for committing a crime. Their expected utility is then the benefit they will get from committing the crime multiplied by the probability of not being arrested, minus the cost of being arrested times the probability of being arrested. In this very simple scenario, our individual will choose the option that maximizes their utility.

In the above equations, there is really only one variable that public policy can’t have any impact on — the benefit of committing crime. All of the other factors are things that can at least be influenced by policymakers.

Often, discussions around how to prevent crime focus on the illegal market side of the equation. The “tough on crime” attitude that rose to the forefront in the 1990s is a hallmark of this type of policymaking. More police and more severe punishments are ways to decrease the expected utility of committing crimes and push some people on the margins towards formal market decisions.

But this isn’t the only approach. Another strategy is to raise the expected value of formal market activity. Higher wages, better hours, more benefits–these are all ways we could discourage crime by making the alternative more appealing.

This is especially true for people who have committed crimes in the past. One major shortcoming of the current criminal justice system is that individuals often experience a significant reduction in their expected utility for formal market employment upon leaving prison. It is more difficult for people with criminal records to find high-quality jobs, making returning to criminal behavior relatively more attractive.

—-

The economic research on the criminal justice system is far deeper than I can go into in a blog post. There are countless issues concerning the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of the criminal justice system that warrant a lot of attention. Hopefully, this has allowed you to see crime through a new lens, where rational actors are making utility maximizing decisions like everyone else in our society. The problem we should be solving is how we can get individual decisions to align with social goals.