How do you feel when you are reading a story you find very interesting, only to hit a snag? It’s a word you don’t know. No, it’s not a new word. It’s a jumble of letters that certainly means something to someone, but not to you. You only know one thing about this jumble of letters: they stand for a phrase that would mean a lot more if it was just written in full.

Yes, you have come across an acronym: the scourge of comprehensible writing everywhere. In a place where an author could have given you a phrase, instead she gave you a vocabulary exercise.

Some technical writing takes the acronym to the extreme. I have seen government or think tank reports that include an entire glossary at the beginning that can be referenced by readers who are not fluent in their particular dialect of Bureaucratese. The author then wipes her hands and continues to write with any range of esoteric acronyms, knowing that the reader can “simply” scroll to the top of the document and locate the abbreviation she doesn’t understand before scrolling back down to the portion of the text she is reading.

The best practice of acronymizing within a report is to write out the full word when using it for the first time, then adding a parenthetical that includes the acronym you intend to use throughout the rest of the document. Theoretically, this allows the reader to internalize the acronym and then recognize that usage throughout the rest of the report.

There are two problems with this approach.

First, if you have to include a parenthetical to explain what an acronym refers to, you are effectively introducing a reader to jargon. If a reader does not fully process the acronym the first time, she will find herself confused as she continues to read and will either have to turn back to locate the first use of the acronym to see what it is referring to or will plow through reading, hoping the acronym isn’t important. If multiple acronyms are used, this gets even worse.

Second, if a reader only reads part of a report, book, or essay, she will not have the context of the first use of the acronym. This is likely to happen in lots of technical writing. If someone is consuming a study, report, or any other type of nonfiction, she often does not have the time to read every word of it and is best served by picking out the parts of it that are most useful to her. If she skimmed over the first establishment of an acronym, later uses of it will just lead to more confusion.

But we do like acronyms. Some of them have infiltrated our language to the point that they have become words in their own right. Some acronyms are commonly used or actually are more clear than the full phrase. For instance, wouldn’t you rather read “DNA” than “deoxyribonucleic acid?”

So what is a writer to do? At Scioto Analysis, we conduct technical writing for a general audience and we write in a field, public policy, that looooves acronyms. So how do we handle these stumbling blocks of clear writing? Below are some tips for guidance for using acronyms in a way that is productive and facilitates the primary goal of writing: clear communication.

Know your audience

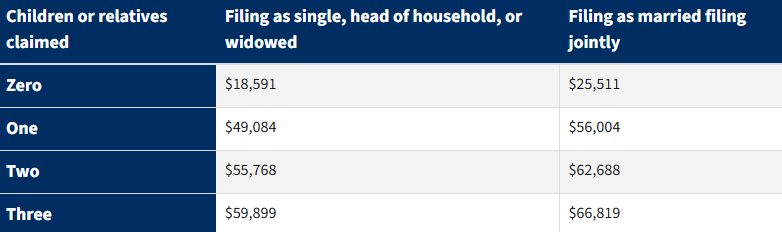

The very most important consideration when using an acronym is audience. If you are writing primarily for an audience that is very familiar with how the tax code impacts people in poverty, you might be good to use the phrase “EITC” in place of “earned income tax credit.” If you think a minority of writers might not be familiar with the phrase, it is probably better to spell it out.

Remember that writing is not the same exercise as speaking. Sure, you may say “EITC” exclusively when you are referring to the earned income tax credit, which is okay when people you are speaking to can clarify the meaning of the term. When writing, the reader cannot ask for that type of clarification from you. So unless you want that reader to do extra work to understand the meaning of what you are writing, spelling out the phrase will make it more clear than using an acronym.

2. Understand the acronym

Another important consideration is which specific acronym you want to use. An acronym like “CDC” or “EPA” are commonly used in public policy and many people outside of the public policy world understand what they mean. Using them is probably less frustrating for a reader than an acronym like the “OECA,” which stands for the Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance, or even worse, the “AOC” when it stands for “Architect of the Capitol,” a federal agency in charge of stewarding public landmarks on Capitol Hill.

Probably the worst offense of all is coining your own acronym. Forcing a reader to learn new vocabulary that did not exist until they read your paper is a capital offense for an analyst who is trying to make concepts more understandable for the readers, not less.

3. Avoid the acronym whenever possible

It is okay to repeat phrases. I repeat: it is okay to repeat phrases. If you say “Department of Transportation" throughout your report instead of “DOT,” even many people who are employed by the Department are not likely to be offended by hearing its name. Most people will not think twice hearing a phrase that is important to your report, analysis, or research over and over again: that is what they expect when they read something on that topic. What people will be offended by is if they have to read a phrase that they do not understand and flip (or more commonly “scroll”) from page to page to figure out what you are talking about.

People in government love to hate acronyms. People outside of government love to hate acronyms in government. Give these people one less thing to hate. Stop using acronyms.